Fatherlessness Shows Up in Children's DNA, Affects Lifespan: Study

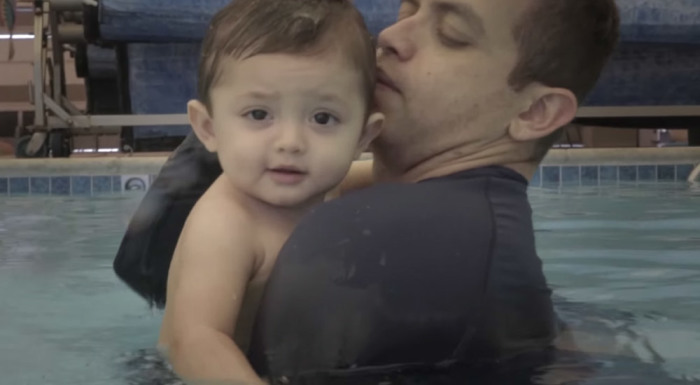

New research shows how the loss of a father significantly affects children — at the level of their DNA, shortening the ends of their chromosomes.

Kids who were raised without a dad have much shorter telomeres, the protective caps at the ends of chromosomes that are believed to affect health and longevity, than kids with fathers in the home, Deseret News reported Tuesday.

The research was done among the approximately 5,000 children who were born between 1998 and 2000 and who are part of the federally-funded Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study. The study was published in the journal "Pediatrics."

For those children whose fathers either died or were incarcerated before they were 5 years old, the effects on their telomeres were most pronounced. Father loss negatively impacted the telomeres of boys 40 percent more than it did on the telomeres of girls.

The study "underscores the important role of fathers in the care and development of children and supplements evidence of the strong negative effects of parental incarceration," the researchers said.

The authors of the study interviewed mothers and fathers when the children were born and subsequently when they were 1, 3, 5 and 9 years old. At age 9, the researchers collected DNA samples from the kids through their saliva; telomere length is often calculated this way.

Nine-year-old children with no dad in the home had telomeres that were 14 percent shorter than children with fathers.

The researchers did discover a bright spot amid their troubling findings, that a stable family income appears to lessen the risk, particularly for children of divorce.

Yet scientists view shortened telomeres as a biological clock, and they are linked with such health issues as mental illness and obesity.

Some scientists believe shorter chromosome caps cause people to age prematurely.

The greatest difference in telomere length could be seen when the reasons for the father loss were examined. Children whose fathers had died had telomeres that were 16 percent shorter than those with living fathers. For children with dads in prison, the reduction averaged 10 percent. For kids whose parents were separated or divorced, their telomeres were 6 percent shorter than those with parents who were together.

The effects of father loss were most visible among boys and children who had a genetic predisposition toward depression, anxiety, or a notable sensitivity to their surroundings, the study noted.

Princeton University's Dr. Daniel Notterman, who co-authored the study, noted his surprise that the children's DNA was impacted so significantly.

"We couldn't test for these, but we have theories. Children need fathers; they're very important. They play an economic role, but also provide love and attention, stability and cohesion, and they're role models," Notterman said.

Telomeres are important in that they function "like a cap on a bicycle valve," the Deseret News article explains.

"They're composed of noncoding DNA, and each time a cell divides, they get smaller. When they get too small, the cell stops dividing and dies."

Other things like chronic stress and a poor diet also shrink telomeres.

But that such external factors like father loss, stress, and diet impact one's DNA like this has surprised acclaimed scientists.

"To an extent that has surprised us and the rest of the scientific community, telomeres do not simply carry out the commands issued by your genetic code," wrote Elizabeth Blackburn in her book The Telomere Effect, which she co-authored with Elissa Epel.

Blackburn is a 2009 Nobel Prize Winner in the field of physiology and medicine for her research on telomeres.

"Your telomeres, as it turns out, are listening to you. They absorb the instructions you give them," she said.