The weaponization of ‘mental health’ and ‘trauma’: A review of Abigail Shrier's 'Bad Therapy'

The woman who journalistically captured a burgeoning epidemic of self-harm among teen girls suddenly identifying as transgender has confronted another colossal behemoth: the mental health industry.

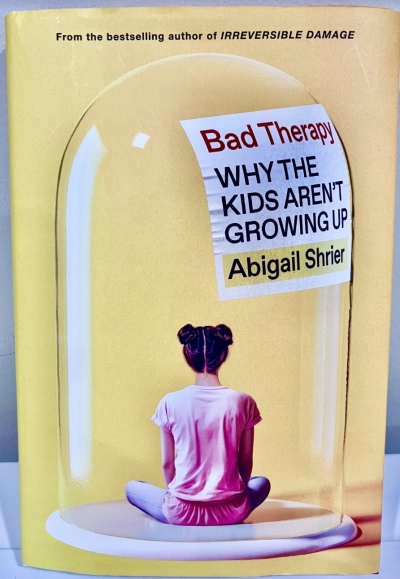

Abigail Shrier’s Bad Therapy: Why the Kids Aren't Growing Up follows her watershed work Irreversible Damage: The Transgender Craze Seducing Our Daughters, which came out in June 2020 amid the COVID-19 pandemic. She has considerably widened her lens for her latest book.

The author begins by explaining how therapists can indeed harm their clients in counseling settings — this is called iatrogenesis — and subsequently examines everything from the psychological disarray that social-emotional learning causes in schools to so-called “gentle” parenting. Also examined are the perils of inculcating kids with “empathy” that, quite perversely, renders them “mean as hell.” At just 12 chapters and 250 pages, the book is a tremendously ambitious and bold undertaking.

So much ground is covered in Bad Therapy it’s hard to know what to highlight first except to say that it’s a remarkably astute catalog documenting how stable structures and standards that we have long relied upon have eroded, all in the name of “mental health.” In an age when seemingly everything is upside-down, Shrier’s agile turn of phrase and lucid prose will make you smile and nod as she unknots many of the most confusing dynamics and troubling forces at work in the worlds of psychology and psychiatry.

Several sacred cows in contemporary culture are substantially scrutinized, and she is unafraid to challenge (if not upend) the prevailing paradigms in the industry. She is not knocking all therapy; good, ethical therapists are out there and they help many people, including some very troubled children. But today’s mental health providers have failed catastrophically on many fronts, the author argues, and it’s more than just the licensed professionals bearing sparkly credentials who are at fault. A much larger shift has occurred culturally.

Generationally, the therapeutic approach to life has transformed child-rearing, saturated parenting books, and has become ubiquitous in schools, Shrier explains. We have on our hands a generation of young people who, though they have had more therapy than any previous generation, are unmotivated, unwell, and unhappy. Even if readers with academic expertise disagree with her analysis on some points, as some have already done, they’d still be hard-pressed to say that her diagnosis that something has gone seriously wrong has no merit because the evidence she marshals is plentiful.

And haven’t we all started to notice this, finally?

For example, under hypertherapeutic regimes where psychologists have been given considerable sway in the schools, numerous “mental health” accommodations have been allowed such that teachers are no longer permitted to dock grades when students turn in homework late. So loosely are these accommodations granted under the auspice of “mental health” that they are now permitted to turn in assignments at the end of the semester if not the end of the school year. Let’s be frank here, kids can be devious little rascals. They know how to game the system and if they can get away with something, they will. Don’t we all know this? The vaunted mental health “experts” shaping our educational institutions sure seem to not understand this anymore.

Teachers are then saddled with the enormously unfair task of having to grade many months' worth of papers all at once. As a result, many who dreamt of being teachers now dream of quitting. One wonders if their "mental health" was ever considered.

An orchestra teacher named David that Shrier interviews tells her that students requesting mental health accommodations say things to him such as “I was having a rough day and dealing with my gender identity” or “I just can’t play [my instrument] today. I’m having a really tough, tough Mental Health Day.” Hearing paltry excuses of this sort, David notes, now “happens all the time.”

This insidious weaponization of mental health doesn’t stop with individual youngsters. It has become a classroom-wide social experiment. Under “restorative justice” practices now being carried out in many schools, students are treated, not disciplined, for terrible behavior. Rarely are they expelled. Among the most egregious of these practices entails young people who were physically bullied being made to face their attacker in front of their peers for the benefit of the entire class.

Such methods — which were championed in a 2014 Obama administration Dear Colleague Letter — are predicated on the belief that all unruly behavior is a cry for help. In an actual bullying scenario, while the offenders are compelled to apologize to the victims, the victims are urged to not only accept the apologies but also offer their own for what they did to provoke the attack. Adding insult to injury, somehow a morally inverted, manipulative reversal like this is supposed to be seen as "restorative."

The realm of “trauma” is perhaps the most significant Goliath that Shrier challenges. While she acknowledges that psychiatric trauma is real, its sufferers endure hellacious torment, and their agony should never be diminished or trivialized, “trauma” has been mischaracterized by prominent therapists. "Childhood trauma” in particular is being cavalierly tossed about as though it is a totalizing answer for whatever problem one might have in life. I know it's anecdotal, and I've only explored these issues a little bit as a journalist and I am still learning, but it's uncanny how many young people I've encountered who now brandish their "trauma" not only as the primary source of all their issues but as a cudgel to foreclose further inquiry about what else might be contributing to their distress.

The intellectual kingpins of trauma, namely Bessel van der Kolk and Gabor Maté, may espouse culturally popular dogmas and sell millions of books (van der Kolk’s famous The Body Keeps the Score has been a mainstay on bestseller lists) but their theories, such as van der Kolk's view that trauma is akin to a "toxin" that is stored in the body, are far from conclusive among professionals in the field, readers of Bad Therapy learn.

Not knowing any better, I have referenced van der Kolk’s words in my own reporting given their seeming authority. To be sure, it is a dicey topic. But it is here where I concur with Baptist theologian Denny Burk who has called upon van der Kolk and his team to respond to Shrier's book because hers is a devastatingly potent critique. Also like Burk, I share his perspective that Christian readers will have their quibbles and will notice worldview differences while reading the book given that Shrier is not a Christian. (She is, however, a most gracious defender of our faith's ideals).

Every so often books come along that are sure to generate long-overdue conversations. Bad Therapy does so by incisively illuminating the problem that many can see but have struggled to find the words for while simultaneously reaffirming the instincts of moms and dads. Parents do indeed know best and only they, not the therapists they have been led to defer to so much, can raise their kids. It is a precious responsibility and their duty to do it well.

If you found Irreversible Damage to be a compelling read as I did, Bad Therapy will open your eyes to the bigger picture. Both books have different focuses and should be read on their own, but it is not hard to see the connection between them and why it made sense for the author to zoom out in the way she did.

As Dr. Hillary Cass’ landmark report on pediatric transgender medicalization in the UK makes ripples worldwide, psychologists are starting to admit that it was their profession that “promoted an ideology that was almost impossible to challenge” and “failed to carry out proper assessments of troubled young people and who failed in their most basic duty to keep proper records.”

Shrier tweeted in response to clinicians who wrote the above-quoted words last week in the Guardian: “The mental health profession – and especially its accrediting organizations — own this catastrophe. They owe the public a full accounting of their failure.”

I couldn’t agree more. I’ve lost count of how many panicked parents I have heard from over the years as they recount to me how ideologically driven therapists hastily referred their psychologically troubled teen daughters for cross-sex hormones or wrote letters for them that greenlighted double mastectomies (Shrier can no doubt relate to what it's like receiving these gut-wrenching phone calls) with no professional attention given to their underlying mental health comorbidities.

If that’s not the ultimate example of bad therapy in action, I don’t know what is.

Brandon Showalter has a bachelor's degree from Bridgewater College in Virginia and a master's degree from The Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C. Listen to Showalter's Generation Indoctrination podcast at The Christian Post and edifi app Send news tips to: brandon.showalter@christianpost.com Follow on Facebook: BrandonMarkShowalter Follow on Twitter: @BrandonMShow