Pakistan passes bill to form National Commission for Minorities after decade of delay

Pakistan’s Parliament has passed a long-delayed law establishing a National Commission for Minorities, marking a step toward institutional protection for religious minorities after years of advocacy and judicial pressure, though the move has prompted only cautious optimism.

The legislation was adopted on Dec. 2 in a joint session, with 160 lawmakers voting in favor and 79 against, amid vocal protests and walkouts from religious parties, according to the United Kingdom-based human rights monitor Center for Legal Aid and Assistance (CLAAS-UK).

The new law creates an 18-member statutory body tasked with investigating violations, advising the government, promoting minority welfare and reviewing implementation of existing legal safeguards.

It follows the Supreme Court’s 2014 directive calling for a commission after a wave of deadly attacks on non-Muslim communities, including Christians.

Debate over the bill revealed divisions over its scope, including the exclusion of Ahmadiyya Muslims, the removal of suo motu powers, and the inclusion of Muslim members on a minorities commission.

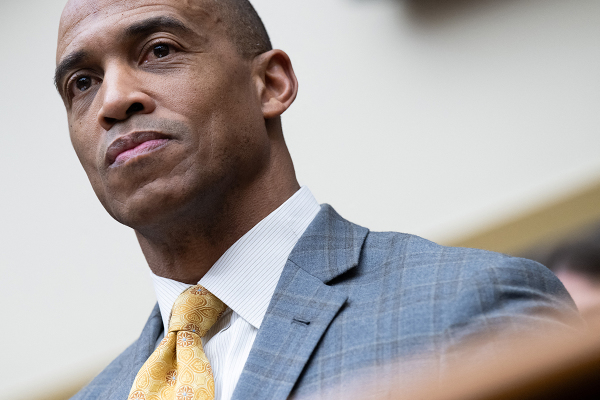

Law Minister Azam Nazeer Tarar defended the law during proceedings, saying it “clearly defines minorities” and reaffirmed that no legislation would be enacted “contrary to the Quran and Sunnah," as quoted by UCA News.

The final version was significantly altered from an earlier draft passed in May, which had included powers allowing the commission to inspect prisons, summon witnesses and initiate investigations without external approval. That version was returned by President Asif Ali Zardari, prompting revisions that removed these provisions.

The revised bill excludes Pakistan’s Ahmadiyya community, which identifies as Muslim but is officially declared non-Muslim by the state.

Tarar stated that the commission’s scope excludes “mischief-makers or those who do not consider themselves non-Muslims,” directly referencing the Ahmadiyya.

The community condemned its exclusion and the language used in parliamentary debates.

“Opposition and even government benches targeted one community and made hate speeches in the National Assembly,” community spokesman Amir Mehmood was quoted as saying. He added that Ahmadis were not consulted and have been deliberately excluded from the commission.

The law stipulates that the prime minister will appoint commission members for three-year terms. It allocates seats for three Hindus, including two from lower caste backgrounds, three Christians, one Sikh, one Baha’i, one Parsee, and two Muslim human rights experts. Each of Pakistan’s four provinces will nominate one representative from its minorities or human rights department, along with one representative from Islamabad.

Human rights groups welcomed the move but expressed concerns over its limitations.

The Human Rights Commission of Pakistan stated on social media that the body must protect all minorities “equally, without exception or hierarchy,” and align with the constitutional guarantees of religious freedom.

Nasir Saeed, director of CLAAS-UK, said the bill’s passage was welcome “even though it comes more than ten years after the Supreme Court first directed the government to establish such a commission.” He acknowledged that rights groups had lobbied for its formation since 2014.

Saeed urged the government to act swiftly to establish the body and ensure it does not become a symbolic institution.

“It should work actively to address forced conversions, coerced marriages, abductions, discrimination, and the misuse of blasphemy laws — issues that continue to cause immense suffering to minority communities in Pakistan,” he said. He also called for transparent functioning, fair representation and adherence to constitutional protections.

Naeem Yousaf Gill, executive director of the National Commission for Justice and Peace, said the move reflected the intent of an “autocratic government” operating under a “paralyzed democracy.” He warned that legal overlaps and political appointments would continue to hinder access to justice for minorities.

Rights advocates have long pointed to systemic issues affecting Pakistan’s Christian, Hindu, and Sikh minorities, who together make up about 4% of the country’s 241.5 million people. These communities have reported frequent cases of forced conversions, coerced marriages, discrimination in public institutions and misuse of blasphemy laws.

The bill was passed during a period of wider concern over democratic regression in the country.

Just weeks earlier, Parliament approved the 27th Constitutional Amendment, which provided Army Chief Field Marshal Asim Munir with lifetime immunity from arrest or prosecution and created a Federal Constitutional Court with authority comparable to that of the Supreme Court.

Religious minorities continue to face barriers to education, employment, and justice, contributing to entrenched poverty and vulnerability to abuse.

Open Doors, an international watchdog organization monitoring persecution in over 60 countries, ranks Pakistan, which has a 97% Muslim population, as the eighth-worst country in the world for Christian persecution on its 2025 World Watch List.