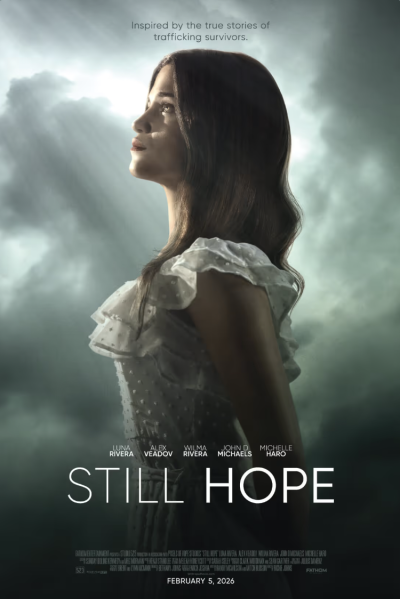

‘Still Hope’ tells story most sex trafficking films don’t: What healing looks like after rescue

Quick Summary

- ‘Still Hope’ explores healing after rescue from sex trafficking.

- Film highlights the recovery process, emphasizing that freedom does not equal healing.

- The project aims to raise awareness and direct viewers to resources for education and survivor support.

For husband-and-wife filmmaking duo Richie and Bethany Johns, the most moving moment in “Still Hope” comes after its protagonist is freed.

Inspired by the real stories of two women who survived sex trafficking, the film opens in familiar territory: a Midwestern town, a churchgoing family, a teenage girl whose life looks ordinary and safe. Hope, 16, meets someone online who isn't who he claims to be. What follows is abduction, coercion, years of abuse and eventually, rescue.

But unlike many films that end merely with survival, “Still Hope” lingers in what comes next.

“The second half of the film is the heart of it,” Richie Johns, who makes his directorial debut with the film, told The Christian Post. “Recovery is a process. Healing takes time. And if we stopped at the rescue, we wouldn’t be telling the true story.”

The idea that freedom is not the same as healing, and that faith plays a key role in recovery, is what ultimately convinced the Johns to take on a project they initially felt unqualified to lead.

When the couple first encountered “Still Hope,” they were approached as producers, tasked with logistics rather than storytelling. A group of Missouri-based filmmakers had been developing the project for years, combining two real-life survivor accounts into a single fictional character. The aim, from the beginning, was to dispel common myths about trafficking: that it happens only overseas, or only to girls who are already vulnerable.

“This was always about showing that it can happen here, domestically,” Richie Johns said. “Hope is a normal girl. Two parents. Goes to church. Lives in an average town. She’s not someone you’d ever expect this to happen to, and that’s exactly the point.”

When executive producer Brent McMinn asked Johns to direct, the decision came with hesitation. Neither Richie nor Bethany, who produced the film, considered themselves experts on trafficking. Both describe their lives as privileged, insulated from the kind of trauma the film depicts.

“We felt deeply inadequate,” Bethany Johns said. “We knew we had a lot of ignorance around this subject, and we had to sit and pray about whether we could tell this story responsibly.”

Bethany had some exposure through a ministry she worked with in college, but even that felt insufficient. What changed was meeting the two women whose lives inspired the film. Listening to them speak, not only about their abuse, but about what came after, reframed the project entirely.

“This was never meant to be a movie just about awareness,” she said. “It was always about hope. About what healing, restoration, even joy can look like after you’ve experienced the worst evils of this world.”

That emphasis is rare in trafficking narratives. “Still Hope,” which stars Luna Rivera, Alex Veadov, Wilma Rivera and John D. Michaels, resists that impulse. Much of the film’s emotional gravity is carried by Rivera’s performance as Hope, particularly in the scenes after she returns home.

“She’s safe, but she’s not OK,” Richie Johns said. “Her family loves her, but they keep saying the wrong things. They want her to be ‘normal’ again. And she can’t.”

One of the film’s most telling moments unfolds on a back porch, where Hope’s mother tries awkwardly, desperately to comfort her with words, even Scripture. Eventually, she stops talking and simply sits.

“That scene is really about presence,” Richie Johns said. “Sometimes it’s not about having the right words. It’s about being willing to sit with someone when they’re not OK.”

The filmmakers were unprepared, they told CP, for the emotional toll of telling the story. Night shoots, heavy subject matter, and the responsibility of honoring real survivors weighed on the cast and crew.

Johns recalled watching Rivera reset emotionally between takes, adding: “I wasn’t ready for how heavy it would be. But we kept reminding ourselves: you have to get people to the second half. You can’t fully understand forgiveness unless you’ve seen what’s being forgiven.”

Forgiveness, a costly, years-long process, is one of the film’s most challenging themes. Both women whose stories inspired Hope told the filmmakers the same thing: they did not experience true freedom until they forgave.

“That shook us,” Bethany Johns said. “Forgiveness isn’t saying what happened was OK. It’s not removing boundaries. It’s saying this won’t have power over me anymore.”

For the Johns, that testimony forced a reckoning with their own faith.

“We talk about forgiveness so easily as Christians,” she said. “But I don’t know that we’ve ever faced something that required that level of forgiveness. This movie made our faith real in a different way.”

Human trafficking remains a widespread issue across the United States. According to the National Human Trafficking Hotline, 9,619 reports of potential cases were received in 2023, involving an estimated 16,999 victims. Advocates say trafficking affects young people of every age, ethnicity and gender in all 50 states and territories.

The film also confronts less visible realities of trafficking, including recidivism. Richie Johns said he was stunned to learn how many survivors return to exploitation after being rescued, often because they have nowhere else to go.

“That’s why recovery centers matter,” he said. “That’s why faith-centered healing matters. Rescue is just the beginning.”

To that end, “Still Hope” was conceived as a call to action. Through partnerships with organizations like the Pure Hope Foundation and others, the project directs viewers to resources for education, prevention and survivor support.

“Trafficking feels overwhelming,” Johns said. “People don’t know how to help. We wanted to move people from awareness to action.”

The women who inspired the story have been involved at every stage, from script development to on-set visits. They have seen the finished film.

“Our hope,” Bethany Johns said, “is that they feel seen. That they feel honored. That they feel like their stories were told with dignity.”

“Still Hope,” distributed by Fathom Entertainment and produced in partnership with Pixels of Hope Studios and Studio 523, opens in theaters nationwide for a limited engagement Feb. 5-9.

Leah M. Klett is a reporter for The Christian Post. She can be reached at: leah.klett@christianpost.com