Christian Nobel winner explains self-interest and altruism

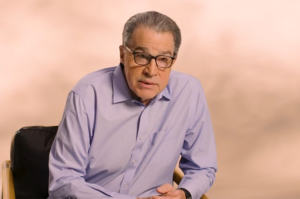

Vernon Smith is many things: a Nobel Prize winner, an economics professor, and the founder of experimental economics, just to name a few. I recently talked with Vernon on my podcast, Meeting of Minds, about his book The Evidence of Things Not Seen. Below are some excerpts from that discussion, edited slightly for length and clarity:

Jerry: What are you learning right now? What’s on your horizon at this moment?

Vernon: The relevance of Adam Smith’s model of human sociability to modern problems. For example, trust games. There’s far more trust and trustworthiness in these two person games then you can get out of the self-interest principle alone. What has baffled us, and what a lot of the behavioral economists have done is simply said: “well, we can explain that if I put your payoff as well as my payoff in my utility function.” But how did it get there? This is not predicting. This is an after effect. You’re curve fitting. You’re fitting to your utility function.

Jerry: Whatever happened must have had utility therefore it fits in the utility function

Vernon: Yeah. Adam Smith was not a utilitarian in that sense at all. In The Theory of Moral Sentiments, everyone is strictly self-interested. But he says you cannot look mankind in the face and avow that every decision is driven by your self interest. So he distinguishes being self-interested from acting always in your self-interest. And that's very important because that opens up the way to us becoming rule followers, in which we use what Adam Smith called self-command, to make judgments about when and where to modify our actions in our self-interest in order to live peaceably with our neighbors.

Jerry: It seems as though the distorted account of Adam Smith plays off self-interest against altruism, whereas in the integrated Adam Smith self-interest is the foundation of altruism. I know getting punched in the nose hurts because if I get punched in the nose it hurts, so I can't really be altruistic unless I've suffered. Unless I know what it is to be a human being in the world. Until then I can’t properly look out for somebody else’s self-interest because they’d be a complete mystery to me.

Vernon: And the rules that we follow have classes: there’s what Adam Smith calls “beneficence and injustice.” These are the two pillars of society. Beneficence has to do with the way we respond when people deliberately do something good for us. When it's intentional, Smith says we feel an obligation to reward that. And injustice has to do with the obverse: somebody does something that’s hurtful to us and intended to do it. We feel the need to punish that in response. Even among friends, when they do things that they didn't intend. They need to be reminded that that's hurtful.

Jerry: Perhaps even beyond the narrow confines of self-interest. In other words, we might pursue justice at cost to ourselves.

Vernon: Think about that, though: if I'm tuned to respond in a reward way to deliberate actions that benefit me, and to punish deliberately hurtful actions, that means that I'm assuming everyone is self-interested. How do you know that people benefit by a particular act? It’s because you’re assuming they’re self-interested.

Jerry: Otherwise what sense does it make to punish someone for doing something bad unless you know that they're not going to like being punished?

Vernon: So self-interest and common knowledge of self-interest is essential in implementing the rules that make us social. And I think this is brilliant! This work was written in 1759, and it’s more relevant, in my view, to understanding these issues of human sociability today than anything comparable that we're now pursuing in the lab, and in our research. It organizes that data really well. Now I'm not saying that there aren't open questions. For example, people don't always read each other perfectly in these games. And so there's room for error, and you see that. But the point is, his model is rich enough that you can vary payoffs to see how that influences the outcome. It's rich enough that you know what to do if and when the model fails.

Jerry Bowyer is financial economist, president of Bowyer Research, and author of “The Maker Versus the Takers: What Jesus Really Said About Social Justice and Economics.”